Difference between revisions of "Landsoftheblacksea:Main Page/players/amara uket"

BlackSeaDM (talk | contribs) |

BlackSeaDM (talk | contribs) |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

Player: OMG | Player: OMG | ||

| + | |||

Character Name: Amara Uk'Et | Character Name: Amara Uk'Et | ||

| + | |||

Race: Human | Race: Human | ||

| + | |||

Class: Cleric 2 | Class: Cleric 2 | ||

| + | |||

Kit: Savage Priest (modified to Detect Abominations instead of Detect Magic, Priest Handbook p107) | Kit: Savage Priest (modified to Detect Abominations instead of Detect Magic, Priest Handbook p107) | ||

| + | |||

Priesthood: Elemental Forces (Priest Handbook p56) | Priesthood: Elemental Forces (Priest Handbook p56) | ||

| + | |||

Faith: Tuathian (https://wiki.rpg.net/index.php/Landsoftheblacksea:Main_Page/religion/elder_elemental) | Faith: Tuathian (https://wiki.rpg.net/index.php/Landsoftheblacksea:Main_Page/religion/elder_elemental) | ||

| + | |||

Alignment: Neutral Good | Alignment: Neutral Good | ||

Strength 11 (Carry 40, Max Press 115, Open Doors 6, Bend Bars 2%) | Strength 11 (Carry 40, Max Press 115, Open Doors 6, Bend Bars 2%) | ||

| + | |||

Dexterity 6 | Dexterity 6 | ||

| + | |||

Constitution 13 (Shock 85%, Resurrection 90%) | Constitution 13 (Shock 85%, Resurrection 90%) | ||

| + | |||

Wisdom 14 (+2 1st spells) | Wisdom 14 (+2 1st spells) | ||

| + | |||

Intelligence 13 (Languages/NWPs +3) | Intelligence 13 (Languages/NWPs +3) | ||

| + | |||

Charisma 3 (2 henchmen, -6 loyalty, -5 reaction) | Charisma 3 (2 henchmen, -6 loyalty, -5 reaction) | ||

| Line 25: | Line 37: | ||

Saving Throws | Saving Throws | ||

| + | |||

Paralyzation, Poison, Death Magic 10 | Paralyzation, Poison, Death Magic 10 | ||

| + | |||

Rod, Staff, or Wand 14 | Rod, Staff, or Wand 14 | ||

| + | |||

Petrification or Polymorph 13 | Petrification or Polymorph 13 | ||

| + | |||

Breath Weapon 16 | Breath Weapon 16 | ||

| + | |||

Spell 15 | Spell 15 | ||

Non-Weapon Proficiencies | Non-Weapon Proficiencies | ||

| + | |||

Fire-Building (Wis -1) | Fire-Building (Wis -1) | ||

| + | |||

Healing (Wis -2) | Healing (Wis -2) | ||

| + | |||

Hunting (Wis -1) | Hunting (Wis -1) | ||

| + | |||

Spellcraft (Int -2) | Spellcraft (Int -2) | ||

| + | |||

Swimming (Str) | Swimming (Str) | ||

| + | |||

Weather Sense (Kit bonus) (Wis -1) | Weather Sense (Kit bonus) (Wis -1) | ||

Weapon Proficiencies | Weapon Proficiencies | ||

| + | |||

Penalty for using weapon I'm not proficient in: -3 | Penalty for using weapon I'm not proficient in: -3 | ||

| + | |||

Spear | Spear | ||

| + | |||

Shortbow | Shortbow | ||

| Line 51: | Line 77: | ||

Hindrances | Hindrances | ||

| + | |||

Savage Priests are strange, primative, and imposing. They suffer a -2 reaction penalty when dealing with any "civilized" people in addition to her -5 from her terrible Charisma. You really want this one talking to people :ROFLMAO: | Savage Priests are strange, primative, and imposing. They suffer a -2 reaction penalty when dealing with any "civilized" people in addition to her -5 from her terrible Charisma. You really want this one talking to people :ROFLMAO: | ||

Magic | Magic | ||

| + | |||

Daily Spells: | Daily Spells: | ||

| + | |||

1st: 4 (2 base + 2 Wisdom) | 1st: 4 (2 base + 2 Wisdom) | ||

| + | |||

Bonus: +1 Elemental spell per day | Bonus: +1 Elemental spell per day | ||

Spheres of Influence | Spheres of Influence | ||

| + | |||

Major: All, Combat, Elemental | Major: All, Combat, Elemental | ||

| + | |||

Minor: Creation, Sun, Weather | Minor: Creation, Sun, Weather | ||

| + | |||

** Access based on Elemental Forces priesthood in the Priests' Handbook | ** Access based on Elemental Forces priesthood in the Priests' Handbook | ||

Money | Money | ||

| + | |||

3d6x5GP (Savage Priest kit) | 3d6x5GP (Savage Priest kit) | ||

| + | |||

Limited to leather armor and shield at the start (Kit requirement) | Limited to leather armor and shield at the start (Kit requirement) | ||

| + | |||

| + | Couple of Questions | ||

| + | |||

| + | Do you count Bow and Shortbow as 2 separate proficiencies? Or do you count them as the same? | ||

| + | |||

| + | I didn't realize until I started building the sheet, but apparently the Elemental Forces priesthood does not get access to the Healing sphere :oops: Could I trade one of my spheres for it? I'm thinking I lose minor access to Creation to get minor access to Healing? | ||

| + | |||

| + | Edit: Wondering if we should consider swapping out Turn Undead, doesn't really fit the concept. Maybe we replace it with something more appropriate for this pantheon? | ||

| + | |||

| + | Amara Uk'Et grew up in the small mountain village of Mobà, located in what in her tongue were called the Fhùall Ununà, and what the lowlanders called the Iron Mountains. Mobà was a small village located deep in the mountains, where the villagers made a subsistence living raising mountain sheep, hunting the live game of the area, growing what vegetables and small crops could handle the short seasons, and trading seasonally, mostly by way of the nomadic raòcbà – gnomes, whose caravans would wander into the village in the summer, bringing cloth and metals and metal goods from the lowlands, and receiving wool and hides and cheeses and mountain herbs in return. The life was hard, but idyllic, with crime virtually unknown, and strong bonds between the families of the small village. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Amara’s mother, Baraball, was a strong, flaxen-haired woman of forty winters who had raised five children, Amara being the middle child. Her father, Adhamh, was a tall, thin shepherd with a kind smile and a contagious laugh, who was well-loved by the other men of the village for his wisdom and even temper. Amara learned what was allowed from her two older brothers, including fighting with spear and shooting with the bow, and taught her two younger sisters the lessons passed down from her mother. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Amara had always been fascinated with the rituals and ceremonies the village celebrated on the holy days – in the summer, the mountain climbs to the secret sites for the offerings to Ishti; in the spring, the gatherings at the springs and pools for the sacrifices to Ulna; in the summer, the games, poetry, and dances to Akazash. But most of all, in the fall, the feasts, the naming ceremonies for the newborn, and the hunts in honor of Laeg. The village was served by two elders who conducted the ceremonies – Tomag, the old wise man, and his wife, Sorcha. The two served as judges, healers, priest and priestess. Tomag acted as a judge in the rare cases where one was needed, and Sorcha was the most skilled healer and midwife in the village. Amara found herself spending much of her free time with Sorcha, eventually learning the rituals and rites of worship for the Four. And learning the oral tradition of their people – their rise, becoming the most advanced civilization in the Lands; the coming of the darkness, when the foul creatures of the beyond appeared; the Elder wars, when the Four and their Tuath servants battled the beyonders, the fate of the Lands in the balance; and the great cataclysm that erupted when the beyonders were driven out, which destroyed the Tuath civilization, reducing it to ruins and dispersing the people that were not killed outright. Of course, these things were stories of things that happened so long ago – who knew what really happened? But it made her smile to think of her people as the savior of the Lands. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then there came the night – just this past fall. The village had just ended the week-long celebration feast to Laeg, and everyone was asleep in their cabins and huts, full of the bounty of the harvest and the summer hunts, tired from the dances, and happy to face the coming winter with full larders. In the dark of night, they came. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The first thing Amara noted when she woke was the lights – there should be no lights in the night. But the flickering light of flame told her something was wrong. Rising, she heard her father telling her mother to gather the girls and prepare to run. He and her brothers were taking their hunting spears, and she saw her father remove the large axe and sword that was hung over the fireplace and grasp them tightly. The family embraced, and then the men exited. She never saw them again. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The screams and shouts from outside made it clear – the village was under attack. Her mother gathered the girls, taking one of the spears herself, and giving Amara her father’s hunting bow and quiver. They exited their home, trying to understand what was happening. | ||

| + | |||

| + | They could see the men -and women, in many cases – of the village engaged in combat with…things. They were not human. They were shorter, and more muscular, with disfigured faces – upturned noses, and tusk-like fangs from the lower jaws. The things wore metal armor, and carried heavy weapons – thick, two-handed axes, heavy-bladed swords, and great hammers. They could hear the screams of the wounded and the guttural yells and laughing from the creatures. The villagers were outnumbered, and it was clear that they would lose. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Baraball hustled the girls down the mountainside, making for the treeline. They moved with the landscape, staying in the shadows where they could. | ||

| + | Just when they thought they might make it, a group of the creatures emerged from the trees they were moving towards, heading upward towards the village. Amara could see the faces beneath the helms, could see the fanged mouths turn up into grotesque, evil smiles. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Without missing a beat, Baraball hurled herself into the creatures. The spear flashed, and the lead creature fell, transfixed by the point, before the others could even react. Amara snapped out of her trance, and began to target the other creatures further from her mother, their armor glinting in the pale moonlight. She dropped one even as her mother turned to a second creature, which had drawn a huge, two-headed axe in both hands. | ||

| + | But it was only a matter of time. Her mother fought valiantly, but the creatures were strong, and not unskilled. Even as Baraball felled a second creature with the spear, XXX saw the blade of the great axe glint, and screamed as it sliced through her mother’s neck, decapitating her. Her mother’s body dropped to its knees, then fell forward, blood still pumping in spurts from the neck. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Amara ran, hustling her sisters before her; but the creatures loped after them, and caught them soon enough. She screamed as the little girls were torn from her hands, one of the creatures pinning her down, its companions laughing and whooping as they tucked the little girls under their arms and took them back, towards the village. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The creature pinning her down leered down at her. In horror, she realized what it intended. Grasping around with her hand, she felt the quiver; she found an arrow. With all her might, she brought it up, jamming the point into the creature’s neck. The eyes bulged as it leapt up, frantically grabbing at its throat. Blood sprayed in gouts from the wound, and it gurgled trying to scream as its throat filled with its own blood. | ||

| + | Amara took the bow, nocked an arrow, and fired at the creature point blank. The arrow struck it at the base of the skull, felling it instantly. She clutched at the weapon, breathing heavily. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Up at the village, the flames were rising. She snatched up the quiver, ran to her mother’s body and took up the spear, then ran up the mountainside to the village. She was sure she would die when she got there, but what else could she do? | ||

| + | |||

| + | When she arrived, it was over. The huts and cabins of the village were in flames. The moans and screams of the dead and dying could barely be heard over the crackling of the fires. The creatures had left – she saw only dead ones. There was no sign of her sisters. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Walking among the bodies, she found her father – together, with one of her brothers. Her brother was dead, his head staved in from the blow of a hammer. Her father bore a huge axe-wound in his chest; his breathing was shallow - it was clear he would be dead within an hour. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Seeing her, he tried to smile, but coughed, blood spewing from his mouth. “…Mother…?” But Amara, eyes filled with tears, could do nothing but shake her head. Adhamh closed his eyes, a tear falling from each of them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As he lay dying, he told her: Go to the sacred site of Ishti, atop the mountain – take the blessed white feather from the shrine there; go to the sacred pool of Ulna, and collect the vial of sacred waters from it; from the clearing in the pine forest, retrieve the carved wooden totem of Laeg; and beneath the ashes of the village great hall, take the everburning rock of Akazash from its place in the fire pit. Take all of these, and carry them to safety – to the Kingdom of the lowlanders, to the east. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “When the time is…right, you will need them to find your brother and sisters - or to avenge our clan. Grow strong. Make allies. The sacred objects will guide you. They will show you the way. They will keep you safe.” | ||

| + | With that, he died. | ||

| + | |||

| + | She made cairns for her family, giving them back to Laeg. For the rest – there were too many bodies for cairns, so she brought them to the village square and built a pyre, returning them to Akazash; not preferred, but better than leaving them for Ishti, and avoiding the worse fate of all, to be swallowed by Ulna and lost forever. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As it burned, the smoke stung her eyes, the smell made her retch. She would find those that did this. She would avenge her village. But she needed help. | ||

| + | |||

| + | She had never left the village before. The journey was hard, but once clear of the mountains, she found wide roads, and as her father had told her, saw the beasts the lowlanders used for transport – oxen and horses, huge compared to the small goats of her village – for the first time, as well as the large carts and caravans they pulled. She saw all manner of creatures her sheltered life had obscured from her – halflings, even a dwarf once. She learned the lowlanders use of coins and currency for almost everything. She started with nothing, and the first weeks were miserable. But she gradually learned that her hunting and healing skills were able to provide her with some funds – very limited, but enough to survive. | ||

| + | |||

| + | She reached the small town of Asala, in the foothills of the mountains, and spent a week there getting her bearings. Asala was home to a huge hall dedicated to the lowlander’s god – an Abbey, they called it, where odd priests called monks lived. Remembering what Tomag and Sorcha had told her about lowlanders and the Elder Gods, Amara kept her faith to herself, trying to fit in as best she could. Ironically, it was one of these lowlander monks – a kind man named Kian Barrett – who became her closest friend in Asala. These monks apparently worked to help the poor, destitute, diseased, and ill – and Amara was definitely poor. Kian was the lead monk in charge of regular offerings of meals to those in need, which Amara took happily, and they became friends. While she ate, Kian told her of places he had been, of things he had seen. The stories were mind-boggling, but Amara filed all the information away for future use. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then one day, he mentioned his time in a city, to the east, on the coast of a great sea – Avis Armois. The descriptions were not sugar coated – this city sounded like it could be dangerous if one wasn’t careful. But it also sounded glamorous, as well as a place where powerful people came and went. Kian mentioned one of his visits into a great swamp nearby the city, and of the ruins he had found inside. But when he described the designs and symbols, she practically choked on her meal. He had almost perfectly described the glyph of Ulna, waves withing a circle. As he went on, she realized this was not coincidence – then the fire of Akazash, then the spirals of Ishti, then the obelisk of Laeg. | ||

| + | |||

| + | That night, her mind raced. Ancient ruins. Tuath symbols. Could the legends be true? What could be found there? Could it help her avenge her village, possibly even find her siblings, if they were alive? | ||

| + | |||

| + | She was gone before dawn the next day. She would go to this city first, and try to find out more about this swamp, these ruins. | ||

| + | She would miss Kian, but knew that she would return here someday – on her way back to her village. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ... | ||

| + | |||

| + | Her journey had been long, but mostly without incident – she travelled along what was called the Southern Reach Road, which ran from Asala in the West to Avis Armois in the East, on the coast. It passed through a number of small villages and towns, none of which were very large – most the size of Asala, or smaller. Sometimes she was able to travel with others – a merchant let her ride on his cart for a time, in return for advice on how to treat his stomach ague; she fell in with a family who were moving to Belis-ar-Weil – a larger settlement north of her destination – who were welcome company for a few days. She even got to walk alongside a gnomish cart train for three days, finding that she enjoyed their jokes and their music, even if she felt sometimes she might be who they talked about when they spoke in their own tongue. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The gnomes she travelled with on the road knew Avis Armois, and told her that if she wanted to know about the Dire Fens, the best people to talk to were the Fenwalkers – a brotherhood of rangers, based out of the city, who patrolled the swamps, keeping track of threats to the surrounding areas and doing their best to keep the evils inside the area contained. They said almost anyone in the city would be able to point her to their hall. | ||

| + | |||

| + | When she asked them about where she should stay, they answered with a question – how much coin did she want to spend, and laughed. In the end, they told her she would probably want to find economic accommodations, and that she should look in the outlying towns or “outer wall” districts, where prices were less steep. The warned her to avoid The Maze, a warren of crime-ridden streets that, while cheap, were not worth the risk. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The entire distance, the road followed the lines of a steep, rocky cliff to its south – a geological feature that everyone called The Fall. Apparently, The Fall was a natural border for the huge, miserable, and terrifying swampland known as The Dire Fens – the same swamp, as far as she could tell, that the monk Kian had been talking about. The Fall surrounded the swamp on three sides, the fourth open to the waters of a large bay of water. She had heard stories of all these kinds of geography in her village – but for the most part, had no experience of them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sometimes the road ran very close to the edge of The Fall, and she was able to gaze down it into the swamps below. The sight was unnerving – the cliff was anywhere from seventy to over one hundred and fifty feet high, and quite steep. There were few places where a road or path cut down from the plains she travelled on into the Fens – and everyone she talked to said that that was something to be thankful for. From the stories, the kinds of creatures that destroyed her village were the best thing one might run into in The Fens. | ||

| + | |||

| + | At night, when they were close to The Fall, she believed the stories. All kinds of terrifying noises came from the misty depths below – screeches, howls, bellows. Once, she awoke to the sound of flapping wings – large wings, not from a bird – and froze, convinced that some horror from below had found her. But the sound receded, and she lived another day. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As the miles past and she moved east, the height of The Fall began to shrink, then finally disappeared altogether. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On her last day, she rose early. A cold, drizzling rain was falling as she trekked the last few miles to the city. A forest appeared to the south, and then the road crossed a very large, wide river. Finally, she crested a small rise, and looked down to see her destination below. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The river which she had crossed spilled out into a vast, swampy delta of sandbars, mudflats, and bonafide islands, and the city was arranged on and around these. Several small villages sat outside the major gates of the City, on ground that looked swampy and prone to flooding. Several buildings that appeared to be slowly crumbling into the marshes and ponds in the area seemed a testament to frequent flooding in the area – the largest of which was the ruins of a large arena of some sort, now collapsing on itself as it sank into a pool outside the city walls. | ||

| + | |||

| + | South of the city proper, the land disintegrated altogether into muck and mire, with the fingers of swamp and land becoming indistinguishable from each other as the ocean reached inland towards the river. | ||

| + | The city appeared to be apportioned into two walled sections, one within the other; the inner section, which looked older than the remainder, housed huge, ancient-looking structures of grandiose scale and ornamentation. One of these buildings, cordoned off by its own wall, was obviously a massive temple – one dedicated to the Holy Faith of Il Matio, judging from the the flowering cross motif ornamentation, which she knew from the Abbey in Asala. There was also a large castle-keep to the south of this section, flying the pennants of the flowering cross as well as that of the Kingdom of Athervon, and others she did not recognize. The walls were huge, made out of some kind of black stone. In the grey drizzle, the place looked depressing and uninviting. | ||

| + | The inner section of the city was surrounded by another walled section, much larger and more spread out than the inner section. The buildings looked to vary between large and expensive in some areas and ramshackle and rundown in others. Wide canals filled with slow-moving, brackish water separated the various sections of the city, connected by ancient-looking bridges of varying lengths. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The city sported several areas with piers and docks, where many large ships were at anchor. More ships sailed in and out of the harbors as she watched, and numerous smaller vessels and barges skirted the wakes and paths of the larger ones. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Several large compounds, surrounded by their own walls, sat outside the walls of the city proper, some at quite a distance. Further away, between them and the city, were fields, now plowed under and empty with the harvest done and the winter on its way. | ||

| + | |||

| + | She moved along down the road towards the city, mixing in with the increasing crowds as they did so. The crowds queued up as they approached the massive main gates and towering walls. The stones were black, whether with age or composition they could not say. The same pennants that flew over the castle hung from the towers on each side of the gate, where towering doors of dark brownish-black wood shod in black iron stood open allowing the crowds to pass in both directions. | ||

| + | Outside the gates were perhaps a half-dozen armed guardsmen dressed in shoddy-looking armor questioning those entering the city and inspecting the carts and baggage of those leaving the city. Each of the guards wears a dirty red surcoat bearing the emblem of a white sword, point down, on the breast, over a chain shirt. They carry heavy iron spears and each wears a thick-bladed broadsword hanging from their belt. Their appearance is somewhat shabby, with greasy hair, stubbly beards, and bloodshot eyes being more common than not. They wave her in without really seeming to notice her. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Entering the city, she finds herself in a large, semi-circular plaza area; the buildings around the outskirts appear to be in various states of repair – some appear quite new and modern looking, while others are dilapidated, shaped from the same mossy, crumbling black stone as the outer walls. | ||

| + | The area is a riot of activity, and she has to move to one side and steady herself with her hand against the dark stone of the gate towers. She has never seen so many people in one place, and the noises, smells, and sights are overwhelming. She sits and just watches for a time, trying to adjust herself to these new environs. Finally, feeling steadier, she rises and looks about her. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Looking around, she sees the road the guard mentioned heading south and west, towards what might be a bridge in the distance. That was the way to Westshore, where she had been told the Fenwalker Hall was. | ||

| + | |||

| + | She crossed the bridges over the canals, through which much of the water from the river flowed before dispersing into the muddy swamps to the south. Shop owner called from their doorways, street vendors yelled the charms of their goods, gangs of urchin children ran about – the activity was dizzying. | ||

| + | Keeping to her directions, she eventually crossed a bridge into a less densely populated area of the city, where the stone favored in the city center gives way to wooden structures, most in the natural shades of wood – pine, ash, and willow predominating. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Turning south, she can see a large building on the eastern side of the street that had to be Fenwalkers Hall. It is built entirely of wood; but rather than the rather rough-hewn look of many of the buildings in this section, this structure was well-made and finished with a high level of craftsmanship – the wooden sheathing on the exterior was tightly fit, and the high, A-framed roof was peaked with stylized carvings of various types of animals. A short set of stairs led to the main doors, and they noted the entire building was set on huge wooden pilings lifting the structure up off the wet, muddy ground that it sat upon next to the city canal. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The doors are open, and she enters the building. | ||

| + | |||

| + | She is in a large, long hallway, lined with wooden pillars that are intricately carved with designs similar to those they saw on the outside. The far side of the room is a large picture window, that looks out over the canal onto the more densely populated city on the far side. Several fireplaces dot the room, all of which are lit with brightly-burning fires. Three large carved wooden chandeliers hang from the ceiling by chains down the center of the room, currently unlit. The room is furnished with a number of tables, some large enough to seat twelve or more, others perhaps two. The chairs are heavy, carved wood, and they note a general lack of cushions anywhere. On the walls are tapestries showing scenes of the wildlands – hills, forests, and of course, swamps. The scenes are typically of a rugged looking individual – some of which are clearly women – traversing the landscape, or sometimes battling a terrifying beast or creature. The smell of pipe-weed is just barely discernable even over the smell of the fires. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Between the tapestries are the objects that truly capture her attention, however: the heads of a number of incredible beasts, apparently preserved and stuffed, are set on wooden frames around the walls. Most are creatures that defy your experience – this one appears nothing more than a huge, frog-like mouth, perhaps 3’ across, bristling with row after row of dagger-like teeth; the next a massive boar-like creature, but outsized, with tusks that are the size of short swords; further on, a coal-black bird, wings outspread spanning nearly 6 feet across, with a huge, serrated beak almost 8 inches long. And so on, and so on. She notes a few doors leading from both sides of this room, but the doors are shut. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A man stands in the room. He is of middle years, his thick black hair not yet showing any grey, but his deeply tanned face lined with more than one crease. He is clean-shaven, with hazel-green eyes. He appears to be of normal height – just under six feet, perhaps – and his build is average, neither thin nor fat. His clothing is plain – a dun-colored cloak, a brown tunic, brown breeches, well-worn leather boots, and leather belt. A sheathed broad sword lays near him on the table, and you can see two daggers – on sheathed on his belt, another in a sheath on his boot. A long, carved wooden pipe, unlit, and a steaming mug of liquid (tea?) sit on the table. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Noticing her entrance, he approaches. “Welcome, Madamoiselle. I am Guillermo Artigas, Master of the Hall.” He bows. | ||

Latest revision as of 14:08, 31 December 2021

Player: OMG

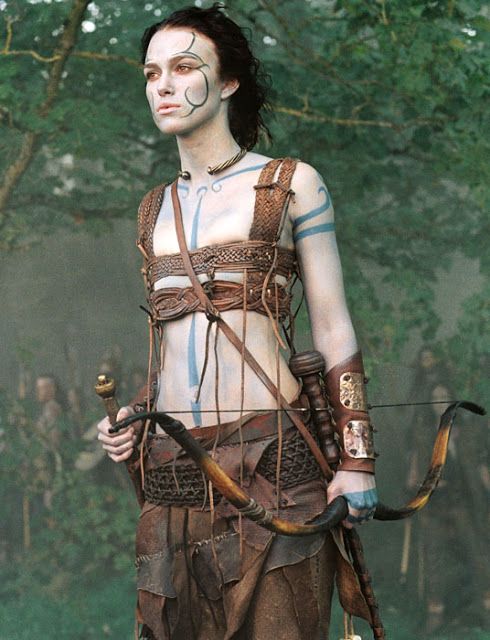

Character Name: Amara Uk'Et

Race: Human

Class: Cleric 2

Kit: Savage Priest (modified to Detect Abominations instead of Detect Magic, Priest Handbook p107)

Priesthood: Elemental Forces (Priest Handbook p56)

Faith: Tuathian (https://wiki.rpg.net/index.php/Landsoftheblacksea:Main_Page/religion/elder_elemental)

Alignment: Neutral Good

Strength 11 (Carry 40, Max Press 115, Open Doors 6, Bend Bars 2%)

Dexterity 6

Constitution 13 (Shock 85%, Resurrection 90%)

Wisdom 14 (+2 1st spells)

Intelligence 13 (Languages/NWPs +3)

Charisma 3 (2 henchmen, -6 loyalty, -5 reaction)

- Stats currently total to 60 because I can't read. Will fix this

Thac0 20

Saving Throws

Paralyzation, Poison, Death Magic 10

Rod, Staff, or Wand 14

Petrification or Polymorph 13

Breath Weapon 16

Spell 15

Non-Weapon Proficiencies

Fire-Building (Wis -1)

Healing (Wis -2)

Hunting (Wis -1)

Spellcraft (Int -2)

Swimming (Str)

Weather Sense (Kit bonus) (Wis -1)

Weapon Proficiencies

Penalty for using weapon I'm not proficient in: -3

Spear

Shortbow

Abilities

Turn Undead (Cleric ability)

Detect Abominations (Savage Priest, 1/day as per a 5th level spell) - Ability to sense the presence of abominations - creatures that are not of this world. Things like aboleths, beholders, illithids, and the like. These creatures, and their gods, are the mythical foes of the Elder Elemental Gods. In the myth circles of the Tuath, it was the struggle between the two that brought on the cataclysm that ended Tuath civilization (paving the way for the other races to dominate the peninsula).

Hindrances

Savage Priests are strange, primative, and imposing. They suffer a -2 reaction penalty when dealing with any "civilized" people in addition to her -5 from her terrible Charisma. You really want this one talking to people :ROFLMAO:

Magic

Daily Spells:

1st: 4 (2 base + 2 Wisdom)

Bonus: +1 Elemental spell per day

Spheres of Influence

Major: All, Combat, Elemental

Minor: Creation, Sun, Weather

- Access based on Elemental Forces priesthood in the Priests' Handbook

Money

3d6x5GP (Savage Priest kit)

Limited to leather armor and shield at the start (Kit requirement)

Couple of Questions

Do you count Bow and Shortbow as 2 separate proficiencies? Or do you count them as the same?

I didn't realize until I started building the sheet, but apparently the Elemental Forces priesthood does not get access to the Healing sphere :oops: Could I trade one of my spheres for it? I'm thinking I lose minor access to Creation to get minor access to Healing?

Edit: Wondering if we should consider swapping out Turn Undead, doesn't really fit the concept. Maybe we replace it with something more appropriate for this pantheon?

Amara Uk'Et grew up in the small mountain village of Mobà, located in what in her tongue were called the Fhùall Ununà, and what the lowlanders called the Iron Mountains. Mobà was a small village located deep in the mountains, where the villagers made a subsistence living raising mountain sheep, hunting the live game of the area, growing what vegetables and small crops could handle the short seasons, and trading seasonally, mostly by way of the nomadic raòcbà – gnomes, whose caravans would wander into the village in the summer, bringing cloth and metals and metal goods from the lowlands, and receiving wool and hides and cheeses and mountain herbs in return. The life was hard, but idyllic, with crime virtually unknown, and strong bonds between the families of the small village.

Amara’s mother, Baraball, was a strong, flaxen-haired woman of forty winters who had raised five children, Amara being the middle child. Her father, Adhamh, was a tall, thin shepherd with a kind smile and a contagious laugh, who was well-loved by the other men of the village for his wisdom and even temper. Amara learned what was allowed from her two older brothers, including fighting with spear and shooting with the bow, and taught her two younger sisters the lessons passed down from her mother.

Amara had always been fascinated with the rituals and ceremonies the village celebrated on the holy days – in the summer, the mountain climbs to the secret sites for the offerings to Ishti; in the spring, the gatherings at the springs and pools for the sacrifices to Ulna; in the summer, the games, poetry, and dances to Akazash. But most of all, in the fall, the feasts, the naming ceremonies for the newborn, and the hunts in honor of Laeg. The village was served by two elders who conducted the ceremonies – Tomag, the old wise man, and his wife, Sorcha. The two served as judges, healers, priest and priestess. Tomag acted as a judge in the rare cases where one was needed, and Sorcha was the most skilled healer and midwife in the village. Amara found herself spending much of her free time with Sorcha, eventually learning the rituals and rites of worship for the Four. And learning the oral tradition of their people – their rise, becoming the most advanced civilization in the Lands; the coming of the darkness, when the foul creatures of the beyond appeared; the Elder wars, when the Four and their Tuath servants battled the beyonders, the fate of the Lands in the balance; and the great cataclysm that erupted when the beyonders were driven out, which destroyed the Tuath civilization, reducing it to ruins and dispersing the people that were not killed outright. Of course, these things were stories of things that happened so long ago – who knew what really happened? But it made her smile to think of her people as the savior of the Lands.

Then there came the night – just this past fall. The village had just ended the week-long celebration feast to Laeg, and everyone was asleep in their cabins and huts, full of the bounty of the harvest and the summer hunts, tired from the dances, and happy to face the coming winter with full larders. In the dark of night, they came.

The first thing Amara noted when she woke was the lights – there should be no lights in the night. But the flickering light of flame told her something was wrong. Rising, she heard her father telling her mother to gather the girls and prepare to run. He and her brothers were taking their hunting spears, and she saw her father remove the large axe and sword that was hung over the fireplace and grasp them tightly. The family embraced, and then the men exited. She never saw them again.

The screams and shouts from outside made it clear – the village was under attack. Her mother gathered the girls, taking one of the spears herself, and giving Amara her father’s hunting bow and quiver. They exited their home, trying to understand what was happening.

They could see the men -and women, in many cases – of the village engaged in combat with…things. They were not human. They were shorter, and more muscular, with disfigured faces – upturned noses, and tusk-like fangs from the lower jaws. The things wore metal armor, and carried heavy weapons – thick, two-handed axes, heavy-bladed swords, and great hammers. They could hear the screams of the wounded and the guttural yells and laughing from the creatures. The villagers were outnumbered, and it was clear that they would lose.

Baraball hustled the girls down the mountainside, making for the treeline. They moved with the landscape, staying in the shadows where they could. Just when they thought they might make it, a group of the creatures emerged from the trees they were moving towards, heading upward towards the village. Amara could see the faces beneath the helms, could see the fanged mouths turn up into grotesque, evil smiles.

Without missing a beat, Baraball hurled herself into the creatures. The spear flashed, and the lead creature fell, transfixed by the point, before the others could even react. Amara snapped out of her trance, and began to target the other creatures further from her mother, their armor glinting in the pale moonlight. She dropped one even as her mother turned to a second creature, which had drawn a huge, two-headed axe in both hands. But it was only a matter of time. Her mother fought valiantly, but the creatures were strong, and not unskilled. Even as Baraball felled a second creature with the spear, XXX saw the blade of the great axe glint, and screamed as it sliced through her mother’s neck, decapitating her. Her mother’s body dropped to its knees, then fell forward, blood still pumping in spurts from the neck.

Amara ran, hustling her sisters before her; but the creatures loped after them, and caught them soon enough. She screamed as the little girls were torn from her hands, one of the creatures pinning her down, its companions laughing and whooping as they tucked the little girls under their arms and took them back, towards the village.

The creature pinning her down leered down at her. In horror, she realized what it intended. Grasping around with her hand, she felt the quiver; she found an arrow. With all her might, she brought it up, jamming the point into the creature’s neck. The eyes bulged as it leapt up, frantically grabbing at its throat. Blood sprayed in gouts from the wound, and it gurgled trying to scream as its throat filled with its own blood. Amara took the bow, nocked an arrow, and fired at the creature point blank. The arrow struck it at the base of the skull, felling it instantly. She clutched at the weapon, breathing heavily.

Up at the village, the flames were rising. She snatched up the quiver, ran to her mother’s body and took up the spear, then ran up the mountainside to the village. She was sure she would die when she got there, but what else could she do?

When she arrived, it was over. The huts and cabins of the village were in flames. The moans and screams of the dead and dying could barely be heard over the crackling of the fires. The creatures had left – she saw only dead ones. There was no sign of her sisters.

Walking among the bodies, she found her father – together, with one of her brothers. Her brother was dead, his head staved in from the blow of a hammer. Her father bore a huge axe-wound in his chest; his breathing was shallow - it was clear he would be dead within an hour.

Seeing her, he tried to smile, but coughed, blood spewing from his mouth. “…Mother…?” But Amara, eyes filled with tears, could do nothing but shake her head. Adhamh closed his eyes, a tear falling from each of them.

As he lay dying, he told her: Go to the sacred site of Ishti, atop the mountain – take the blessed white feather from the shrine there; go to the sacred pool of Ulna, and collect the vial of sacred waters from it; from the clearing in the pine forest, retrieve the carved wooden totem of Laeg; and beneath the ashes of the village great hall, take the everburning rock of Akazash from its place in the fire pit. Take all of these, and carry them to safety – to the Kingdom of the lowlanders, to the east.

“When the time is…right, you will need them to find your brother and sisters - or to avenge our clan. Grow strong. Make allies. The sacred objects will guide you. They will show you the way. They will keep you safe.” With that, he died.

She made cairns for her family, giving them back to Laeg. For the rest – there were too many bodies for cairns, so she brought them to the village square and built a pyre, returning them to Akazash; not preferred, but better than leaving them for Ishti, and avoiding the worse fate of all, to be swallowed by Ulna and lost forever.

As it burned, the smoke stung her eyes, the smell made her retch. She would find those that did this. She would avenge her village. But she needed help.

She had never left the village before. The journey was hard, but once clear of the mountains, she found wide roads, and as her father had told her, saw the beasts the lowlanders used for transport – oxen and horses, huge compared to the small goats of her village – for the first time, as well as the large carts and caravans they pulled. She saw all manner of creatures her sheltered life had obscured from her – halflings, even a dwarf once. She learned the lowlanders use of coins and currency for almost everything. She started with nothing, and the first weeks were miserable. But she gradually learned that her hunting and healing skills were able to provide her with some funds – very limited, but enough to survive.

She reached the small town of Asala, in the foothills of the mountains, and spent a week there getting her bearings. Asala was home to a huge hall dedicated to the lowlander’s god – an Abbey, they called it, where odd priests called monks lived. Remembering what Tomag and Sorcha had told her about lowlanders and the Elder Gods, Amara kept her faith to herself, trying to fit in as best she could. Ironically, it was one of these lowlander monks – a kind man named Kian Barrett – who became her closest friend in Asala. These monks apparently worked to help the poor, destitute, diseased, and ill – and Amara was definitely poor. Kian was the lead monk in charge of regular offerings of meals to those in need, which Amara took happily, and they became friends. While she ate, Kian told her of places he had been, of things he had seen. The stories were mind-boggling, but Amara filed all the information away for future use.

Then one day, he mentioned his time in a city, to the east, on the coast of a great sea – Avis Armois. The descriptions were not sugar coated – this city sounded like it could be dangerous if one wasn’t careful. But it also sounded glamorous, as well as a place where powerful people came and went. Kian mentioned one of his visits into a great swamp nearby the city, and of the ruins he had found inside. But when he described the designs and symbols, she practically choked on her meal. He had almost perfectly described the glyph of Ulna, waves withing a circle. As he went on, she realized this was not coincidence – then the fire of Akazash, then the spirals of Ishti, then the obelisk of Laeg.

That night, her mind raced. Ancient ruins. Tuath symbols. Could the legends be true? What could be found there? Could it help her avenge her village, possibly even find her siblings, if they were alive?

She was gone before dawn the next day. She would go to this city first, and try to find out more about this swamp, these ruins. She would miss Kian, but knew that she would return here someday – on her way back to her village.

...

Her journey had been long, but mostly without incident – she travelled along what was called the Southern Reach Road, which ran from Asala in the West to Avis Armois in the East, on the coast. It passed through a number of small villages and towns, none of which were very large – most the size of Asala, or smaller. Sometimes she was able to travel with others – a merchant let her ride on his cart for a time, in return for advice on how to treat his stomach ague; she fell in with a family who were moving to Belis-ar-Weil – a larger settlement north of her destination – who were welcome company for a few days. She even got to walk alongside a gnomish cart train for three days, finding that she enjoyed their jokes and their music, even if she felt sometimes she might be who they talked about when they spoke in their own tongue.

The gnomes she travelled with on the road knew Avis Armois, and told her that if she wanted to know about the Dire Fens, the best people to talk to were the Fenwalkers – a brotherhood of rangers, based out of the city, who patrolled the swamps, keeping track of threats to the surrounding areas and doing their best to keep the evils inside the area contained. They said almost anyone in the city would be able to point her to their hall.

When she asked them about where she should stay, they answered with a question – how much coin did she want to spend, and laughed. In the end, they told her she would probably want to find economic accommodations, and that she should look in the outlying towns or “outer wall” districts, where prices were less steep. The warned her to avoid The Maze, a warren of crime-ridden streets that, while cheap, were not worth the risk.

The entire distance, the road followed the lines of a steep, rocky cliff to its south – a geological feature that everyone called The Fall. Apparently, The Fall was a natural border for the huge, miserable, and terrifying swampland known as The Dire Fens – the same swamp, as far as she could tell, that the monk Kian had been talking about. The Fall surrounded the swamp on three sides, the fourth open to the waters of a large bay of water. She had heard stories of all these kinds of geography in her village – but for the most part, had no experience of them.

Sometimes the road ran very close to the edge of The Fall, and she was able to gaze down it into the swamps below. The sight was unnerving – the cliff was anywhere from seventy to over one hundred and fifty feet high, and quite steep. There were few places where a road or path cut down from the plains she travelled on into the Fens – and everyone she talked to said that that was something to be thankful for. From the stories, the kinds of creatures that destroyed her village were the best thing one might run into in The Fens.

At night, when they were close to The Fall, she believed the stories. All kinds of terrifying noises came from the misty depths below – screeches, howls, bellows. Once, she awoke to the sound of flapping wings – large wings, not from a bird – and froze, convinced that some horror from below had found her. But the sound receded, and she lived another day.

As the miles past and she moved east, the height of The Fall began to shrink, then finally disappeared altogether.

On her last day, she rose early. A cold, drizzling rain was falling as she trekked the last few miles to the city. A forest appeared to the south, and then the road crossed a very large, wide river. Finally, she crested a small rise, and looked down to see her destination below.

The river which she had crossed spilled out into a vast, swampy delta of sandbars, mudflats, and bonafide islands, and the city was arranged on and around these. Several small villages sat outside the major gates of the City, on ground that looked swampy and prone to flooding. Several buildings that appeared to be slowly crumbling into the marshes and ponds in the area seemed a testament to frequent flooding in the area – the largest of which was the ruins of a large arena of some sort, now collapsing on itself as it sank into a pool outside the city walls.

South of the city proper, the land disintegrated altogether into muck and mire, with the fingers of swamp and land becoming indistinguishable from each other as the ocean reached inland towards the river. The city appeared to be apportioned into two walled sections, one within the other; the inner section, which looked older than the remainder, housed huge, ancient-looking structures of grandiose scale and ornamentation. One of these buildings, cordoned off by its own wall, was obviously a massive temple – one dedicated to the Holy Faith of Il Matio, judging from the the flowering cross motif ornamentation, which she knew from the Abbey in Asala. There was also a large castle-keep to the south of this section, flying the pennants of the flowering cross as well as that of the Kingdom of Athervon, and others she did not recognize. The walls were huge, made out of some kind of black stone. In the grey drizzle, the place looked depressing and uninviting. The inner section of the city was surrounded by another walled section, much larger and more spread out than the inner section. The buildings looked to vary between large and expensive in some areas and ramshackle and rundown in others. Wide canals filled with slow-moving, brackish water separated the various sections of the city, connected by ancient-looking bridges of varying lengths.

The city sported several areas with piers and docks, where many large ships were at anchor. More ships sailed in and out of the harbors as she watched, and numerous smaller vessels and barges skirted the wakes and paths of the larger ones.

Several large compounds, surrounded by their own walls, sat outside the walls of the city proper, some at quite a distance. Further away, between them and the city, were fields, now plowed under and empty with the harvest done and the winter on its way.

She moved along down the road towards the city, mixing in with the increasing crowds as they did so. The crowds queued up as they approached the massive main gates and towering walls. The stones were black, whether with age or composition they could not say. The same pennants that flew over the castle hung from the towers on each side of the gate, where towering doors of dark brownish-black wood shod in black iron stood open allowing the crowds to pass in both directions. Outside the gates were perhaps a half-dozen armed guardsmen dressed in shoddy-looking armor questioning those entering the city and inspecting the carts and baggage of those leaving the city. Each of the guards wears a dirty red surcoat bearing the emblem of a white sword, point down, on the breast, over a chain shirt. They carry heavy iron spears and each wears a thick-bladed broadsword hanging from their belt. Their appearance is somewhat shabby, with greasy hair, stubbly beards, and bloodshot eyes being more common than not. They wave her in without really seeming to notice her.

Entering the city, she finds herself in a large, semi-circular plaza area; the buildings around the outskirts appear to be in various states of repair – some appear quite new and modern looking, while others are dilapidated, shaped from the same mossy, crumbling black stone as the outer walls. The area is a riot of activity, and she has to move to one side and steady herself with her hand against the dark stone of the gate towers. She has never seen so many people in one place, and the noises, smells, and sights are overwhelming. She sits and just watches for a time, trying to adjust herself to these new environs. Finally, feeling steadier, she rises and looks about her.

Looking around, she sees the road the guard mentioned heading south and west, towards what might be a bridge in the distance. That was the way to Westshore, where she had been told the Fenwalker Hall was.

She crossed the bridges over the canals, through which much of the water from the river flowed before dispersing into the muddy swamps to the south. Shop owner called from their doorways, street vendors yelled the charms of their goods, gangs of urchin children ran about – the activity was dizzying. Keeping to her directions, she eventually crossed a bridge into a less densely populated area of the city, where the stone favored in the city center gives way to wooden structures, most in the natural shades of wood – pine, ash, and willow predominating.

Turning south, she can see a large building on the eastern side of the street that had to be Fenwalkers Hall. It is built entirely of wood; but rather than the rather rough-hewn look of many of the buildings in this section, this structure was well-made and finished with a high level of craftsmanship – the wooden sheathing on the exterior was tightly fit, and the high, A-framed roof was peaked with stylized carvings of various types of animals. A short set of stairs led to the main doors, and they noted the entire building was set on huge wooden pilings lifting the structure up off the wet, muddy ground that it sat upon next to the city canal.

The doors are open, and she enters the building.

She is in a large, long hallway, lined with wooden pillars that are intricately carved with designs similar to those they saw on the outside. The far side of the room is a large picture window, that looks out over the canal onto the more densely populated city on the far side. Several fireplaces dot the room, all of which are lit with brightly-burning fires. Three large carved wooden chandeliers hang from the ceiling by chains down the center of the room, currently unlit. The room is furnished with a number of tables, some large enough to seat twelve or more, others perhaps two. The chairs are heavy, carved wood, and they note a general lack of cushions anywhere. On the walls are tapestries showing scenes of the wildlands – hills, forests, and of course, swamps. The scenes are typically of a rugged looking individual – some of which are clearly women – traversing the landscape, or sometimes battling a terrifying beast or creature. The smell of pipe-weed is just barely discernable even over the smell of the fires.

Between the tapestries are the objects that truly capture her attention, however: the heads of a number of incredible beasts, apparently preserved and stuffed, are set on wooden frames around the walls. Most are creatures that defy your experience – this one appears nothing more than a huge, frog-like mouth, perhaps 3’ across, bristling with row after row of dagger-like teeth; the next a massive boar-like creature, but outsized, with tusks that are the size of short swords; further on, a coal-black bird, wings outspread spanning nearly 6 feet across, with a huge, serrated beak almost 8 inches long. And so on, and so on. She notes a few doors leading from both sides of this room, but the doors are shut.

A man stands in the room. He is of middle years, his thick black hair not yet showing any grey, but his deeply tanned face lined with more than one crease. He is clean-shaven, with hazel-green eyes. He appears to be of normal height – just under six feet, perhaps – and his build is average, neither thin nor fat. His clothing is plain – a dun-colored cloak, a brown tunic, brown breeches, well-worn leather boots, and leather belt. A sheathed broad sword lays near him on the table, and you can see two daggers – on sheathed on his belt, another in a sheath on his boot. A long, carved wooden pipe, unlit, and a steaming mug of liquid (tea?) sit on the table.

Noticing her entrance, he approaches. “Welcome, Madamoiselle. I am Guillermo Artigas, Master of the Hall.” He bows.