Tyche's Favourites/Massalia: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

'''Massalia in 300BC''' | '''Massalia in 300BC''' | ||

Massalia is one of the largest trading ports in the bowl of the world, with a population of some 6,000 and a stone wall encircling its fifty hectares of land. It is situated on a hill overlooking the cove of Lakydon which is fed by a freshwater stream and protected by two rocky promontories. | Massalia is one of the largest trading ports in the bowl of the world, with a population of some 6,000 and a stone wall encircling its fifty hectares of land. It is situated on a hill overlooking the cove of Lakydon which is fed by a freshwater stream and protected by two rocky promontories. It has a large temple of the cult of Apollo of Delphi on a hilltop overlooking the port, and a temple of the cult of Artemis of Ephesus at the other end of the city. | ||

''Society'' | |||

Like many expatriots, Massilioi like to think of themselves as authentic Greeks, trying to preserve their identity to the exclusion of local Keltic influences. It is for this reason that only those of Greek ancestry can be recognised as citizens, with the sizable local Kelto-Hellenic population excluded from citizenship. As in any other Greek polis, only free Greek males may participate directly in political life, in return for military service. Theoretically, every member of the council (or their sons in the case of older men) is liable to be called up to fight should the city be threatened. However, the reality is that Massilioi prefer to let others do their fighting for them, co-opting the local tribes, and when all else fails seeking assistance from the Roman Republic. | |||

Ultimately, Massalia is an affluent city prospering through trade, and its aristocrats and other worthy men are more interested in profit than anything else. | |||

| Line 38: | Line 46: | ||

''Economy'' | |||

Trade was Massalia's lifeblood. They exported their own products; local wine, salted pork and fish, aromatic and medicinal plants, coral and cork, salt, olive oil, cups, mixing bowls, to inland markets in Gallia. They were a destination for re-export primarily of grain, amber, tin and slaves. | |||

[[Tyche's_Favourites |Back to main page]] | [[Tyche's_Favourites |Back to main page]] | ||

Revision as of 22:52, 19 June 2013

Foreigners in Southern Gallia

The coast of modern-day Provence has some of the earliest known sites of human habitation in Europe, dating back to pre-human hominids around 1 million BC. There is evidence of continued habitation, and repeated migration of other peoples, sometimes displacing the natives. Between the 10th and 4th centuries BC, the dominant peoples were the Ligures. They are of uncertain origins, possibly descendants of the indigenous neolithic people, but ancient commentators were certain they were not Keltoi. They were not literate, but had their own Indo-European language. They were a warlike and mobile people, and invaded Italy from time to time.

Between the 8th and 5th centuries BC, tribes of Keltic peoples, probably coming from Central Europe, also began moving into Provence. They had weapons made of iron, which allowed them to easily defeat the local tribes, who were still armed with bronze weapons. One tribe, called the Segobriga, settled near Massalia. The Caturiges, Tricastins, and Cavares settled to the west of the Druentia river.

Keltoi and Ligures lived widely widespread in Provence and the Kelto-Ligures eventually shared the territory of Provence, each tribe in its own alpine valley or settlement along a river, each with its own king and dynasty. They built hilltop forts and settlements, later given the Latin name oppida. They worshipped various aspects of nature, establishing sacred woods at Sainte-Baume and Gemenos, and healing springs at Glanum and Vernėègues. Later, in the 5th and 4th centuries BC, the different tribes formed confederations; the Voconces in the from the Isère to the Vaucluse; the Cavares in the Comtat; and the Salyens, from the Rhone river to the Var. The tribes began to trade their local products, iron, silver, alabaster, marble, gold, resin, wax, honey and cheese; with their neighbors, first by trading routes along the Rhone river, and later Tyrrhenoi traders visited the coast.

The Tyrrhenoi were the first of many foreigners to arrive seeking opportunities in trade, though they never settled, preferring to trade off their ships. At this time the Phoenicians were also setting up trading posts throughout the western Mediterranean (primarily the islands and the coasts of Iberia), and between them the two peoples dominated trade in the Gulf of Lion. The first to found permanent posts in Provence were Greeks. Traders from the island of Rhodes were visiting the coast of Provence in the 7th century BC, bringing pottery and luxury goods. They gave their name to the Rhodanos river and founded Rhodanousia. Some time later, the colony of Theline was founded on the other fork of the Rhodanos.

Massalia's Early History

In around 600BC, Greeks from the Ionian city of Phokaia founded a trading port on the southern coast of Gallia. The precise circumstances and date of Massalia's founding is a mystery, but a legend persists. Protis, while exploring for a new trading outpost or emporion for Phocaea, discovered the Mediterranean cove of the Lakydon. Protis was invited inland to a banquet held by the chief of the local Ligurian tribe for suitors seeking the hand of his daughter Gyptis in marriage. At the end of the banquet, Gyptis presented the ceremonial cup of wine to Protis, indicating her unequivocal choice. Following their marriage, they moved to the hill just to the north of the Lacydon; and from this settlement grew Massalia.

Massalia was one of the first Greek ports in Western Europe and was the first settlement given city status in Gallia. A number of other colonies followed, including Agathe Tyche, Emporion and Rhode in Iberia and Alalia on Kurtyn (Corsica). This common mother city helped foster trading links between those Phokaian-founded settlements and Massalia. However, the Carthaginians and Etruscans did not accept the rising commercial power of Massalia lightly, and after a costly naval victory, the colonists were driven off Kurtyn. In around 540BC, a second wave of colonists from Phokaia arrived, fleeing destruction of that city at the hands of the Persians, many eventually settling at Elea in Italia.

Facing an opposing alliance of the Etruscans, Carthage and the Celts, the Greek colony allied itself with the expanding Roman Republic for protection. This protectionist association brought aid in the event of future attacks, and perhaps equally important, it also brought the people of Massalia into the complex Roman market. The city thrived by acting as a link between inland Gaul, hungry for Roman goods and wine, and Rome's insatiable need for new products and slaves.

Massalia founded colonies of its own, largely to secure its trade routes and ensure safe places for ships to take on food and water, and shelter against bad weather. They covered a sweep of villages and towns along the southern coast of Gallia, including Tauroeis, Olbia, Antipolis, Nikaia and Monoikos.

Some time between 330BC and 320BC, the mathematician, astronomer and navigator Pytheas set off on his famous voyage through the Pillars of Herakles and into the northern waters around Alba (Britain) and Scandia. He hoped to establish an alternate trading route for tin from Alba, but it was cheaper and simpler to continue trading over land routes.

Massalia in 300BC

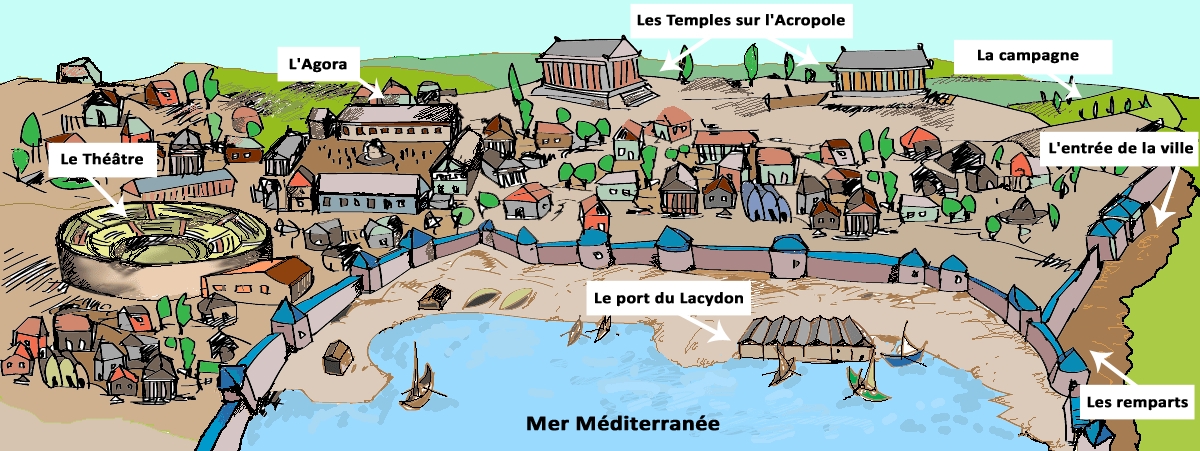

Massalia is one of the largest trading ports in the bowl of the world, with a population of some 6,000 and a stone wall encircling its fifty hectares of land. It is situated on a hill overlooking the cove of Lakydon which is fed by a freshwater stream and protected by two rocky promontories. It has a large temple of the cult of Apollo of Delphi on a hilltop overlooking the port, and a temple of the cult of Artemis of Ephesus at the other end of the city.

Society

Like many expatriots, Massilioi like to think of themselves as authentic Greeks, trying to preserve their identity to the exclusion of local Keltic influences. It is for this reason that only those of Greek ancestry can be recognised as citizens, with the sizable local Kelto-Hellenic population excluded from citizenship. As in any other Greek polis, only free Greek males may participate directly in political life, in return for military service. Theoretically, every member of the council (or their sons in the case of older men) is liable to be called up to fight should the city be threatened. However, the reality is that Massilioi prefer to let others do their fighting for them, co-opting the local tribes, and when all else fails seeking assistance from the Roman Republic.

Ultimately, Massalia is an affluent city prospering through trade, and its aristocrats and other worthy men are more interested in profit than anything else.

Government

Initially, the Massilian constitution was a narrow aristocratic regime. However, an attempt was soon made to reduce the power of the great families by insisting that, if a man belong to the Council his son could not, and if an elder brother belonged to the Council his younger brother could not be a member. Such specifics probably lapsed, but the tendency led to the evolution of the aristocratic system to a more plutocratic oligarchic system. This government is headed by the Council of Six Hundred. To be a member councilors has to be able to prove they were of citizen decent for at least three generations or, alternatively, has to possess children. The list is revised from time to time. The Council elects an executive council of fifteen— oi timoukoi—from the main body. The timouchoi are led by three presidents. An unusual feature of the Massilian government is that a criminal condemned to death is maintained at public expense for one year, after which the criminal is executed as a pharmakos or purification of the city.

Economy

Trade was Massalia's lifeblood. They exported their own products; local wine, salted pork and fish, aromatic and medicinal plants, coral and cork, salt, olive oil, cups, mixing bowls, to inland markets in Gallia. They were a destination for re-export primarily of grain, amber, tin and slaves.