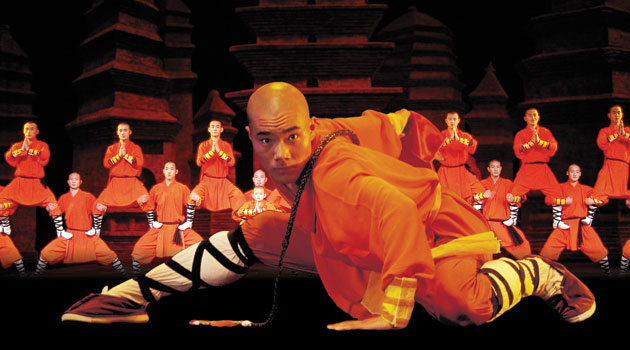

The World of Kung-Fu 3.1: Shaolin

Shaolin Monks

“How many Shaolin monks does it take to change a lightbulb?”

“None”—Shaolin riddle.

The Shaolin are legendary both for the power of their Kung Fu and the nobility of their character. They are seen as epitomes of virtue, dedication, courage, and compassion. If anything stands as a symbol for good in the world, it is the Shaolin monk (or nun—there is a Shaolin nunnery deeper in the Songshan Mountains). What’s more, Shaolin Kung Fu is the most influential in history. Most Kung Fu are descended from it, with the only known exceptions being those descended solely from Wudang Kung Fu (the most prominent of which are Hsing I Chuan, Pa Kua Chuan and Tai Chi Chuan).

The reverence with which the Shaolin are treated suits their self-image well. They regard themselves as the wisest people in the world and wish that humanity had the sense to do what the Shaolin tell them to do and live how the Shaolin tell them to live. Shaolin agents, especially monks, are often woefully naïve and ignorant about practical matters.

The Shaolin’s plan for winning the Kung Fu War and saving humanity is to convert the world to Buddhism, and through Buddhism, to make humanity kind and virtuous. They have had little success. In the US, Shaolin agents have been working as Buddhist missionaries since the early 1800s but have made very few converts.1

“I love being a monk. I can practice Kung Fu all day and instead of feeling guilty about it, I feel righteous!”—anonymous.

It is difficult to find a teacher of genuine Shaolin Kung Fu in the US, and being Trained by a Master requires being trained at the Shaolin Monastery in China, and usually, becoming a Shaolin monk. However, sometimes the monks will take pity and train a lay person who has been wronged and is badly in need of Kung Fu to protect innocents. The Shaolin take it as read that anyone they train in the secrets of their art can be called on to serve the monastery at any time. All applications to join the Shaolin must be made in person at the Shaolin Monastery by someone who has come a long way on foot. Officially, once someone has become a monk, they have no right to quit. In practice, the Shaolin do not arrest rogue monks who turn their back on their vows and enter the secular world. However, they do shame them and exhort them to return to their duties. In practice, few monks wish to leave. Thanks to the compassionate nature of the Shaolin and to their healthy lifestyle, Shaolin Monastery is a notoriously happy place.2

Common professions: Beggar, manual laborer, monk.

Q: “A Shaolin and a Thai monk agree to have a car race to Nirvana. Who wins?”

A: “The Shaolin. He has the greater vehicle.”

Q: “Why did the Shaolin monk crash his car?”

A: “He let go of the wheel”—Shaolin riddle.

Shaolin Relations

Wing Chun: For the Shaolin, Wing Chun represents something close to a secular ideal. Not everybody can be a monk or priest, but everyone should live a life of duty, order, discipline, honor and respect for tradition: the very values around which most Wing Chun schools are organized. Wing Chun’s ally Kuntao is seen as less disciplined and polished, but as sharing the same basic values. Hung Gar’s rejection of all non-Kung Fu authority is too radical for the Shaolin, who think Hung Gar hot-headed and intemperate. Still, Hung Gar’s close Shaolin roots and tireless fighting in the Kung Fu War make the monks fond of it. Jeet Kune Do rejects the Shaolin for their imprisonment of Bruce Lee. This hurts the monks’ feelings, but they forgive Jeet Kune Do and want them to return to the fold.

Wudang: The Shaolin understand that the Wudang are fundamentally compassionate and mean to be on the side of good, but they find the priests insufferably smug. What’s worse, the Wudang sometimes get in the way of fighting the Kung Fu War by resisting Shaolin authority over the Wulin, while providing very little in the way of plans or leadership themselves.3 Wudang allies Hsing I Chuan and Pa Kua Chuan are not antagonistic to the Shaolin, but nor do they regard them as particularly wise, which irritates the Shaolin no end. Tai Chi, on the other hand, goes out of its way to pay respect to the monks, and the Shaolin treat Tai Chi as friends in return.

Vigilantes: Because the Vigilantes have no particular commitment to Buddhist rules and values, the Shaolin hierarchy has difficulty seeing that they have rules and values at all. From the Shaolin Monastery, American Vigilantism looks like a random outburst of animal violence. Shaolin agents who live in America have a better understanding, and generally know that the Vigilantes mean to be good guys. Shaolin agents even sometimes cooperate with Vigilante teams out in the field. Still, the Shaolin don’t trust Vigilantes too far. They view them as ignorant, undisciplined and excitable people with dangerous abilities.

A Shaolin monk seats himself in a tea house and the waiter asks him, “What would you like?” And the monk says, “A cup of tea and some hot Hunan noodles.” (Sounds like, “Nothing. With our thoughts, we make the world.”)—Ming Dynasty joke, ca. 1450.

Shaolin Allies

While the Shaolin faction is led by the Shaolin monks, most faction members come from allied styles. The three most important allied faction styles are Kempo, Pak Hok, and Praying Mantis.

Kempo

“Nonviolence has an army. That army’s name is Shorinji Kempo”—Doshin So, Kempo Master, Just So, 1948.

“Nonviolence has an army. That army’s name is Shorinji Kempo”—Doshin So, Kempo Master, Just So, 1948.

Shorinji Kempo was introduced to the secular world by Japanese Buddhist monks after World War II, in an effort to reinvigorate Buddhist values in Japan. Today, the style is popular enough in the US to provide most of the Shaolin faction’s troops. Insofar as the Shaolin can field an “army”, it will mostly be composed of Kempo students. Kempo is not as selective in accepting students as other Shaolin faction styles precisely because they understand the importance of numbers in battle. To the horror of traditional Kempo artists, the effectiveness of the style has attracted the attention of martial artists who care nothing about Buddhism and just want to kick butt.

Kempo sees itself as the natural leader of the Japanese styles. It strives to end the Karate Wars by convincing the Karateka to focus on Buddhism. Of all the Shaolin faction, Kempo fighters are the least resistant to working with Vigilantes. Kempo understands some of the harsh realities of the Kung Fu War as it is raging on the streets of America, and know how useful it can be to have Vigilante allies, as imperfect as they are.

For members of the Shaolin faction, Kempo fighters have a reputation for being streetwise and technologically competent, and for urging the rest of the faction to get up to date.

Common Professions: Any.

Pak Hok

“There’s nothing tougher than a Tibettan monk. The cold, the wind, the snow on top of those mountains, and they all walk around barefoot! They are monks’ monks up there. Hence Pak Hok”—Tathagat, Abbot of Shaolin, Manchu Dynasty, 1655.

Invented by Tibetan monks, Pak Hok, or “White Crane Kung Fu”, is a Tibetan development of Shaolin Kung Fu, based on observation of Cranes. Pak Hok’s proven effectiveness in combat has attracted some western students who just want to win fights, and couldn’t care less about Buddhism or monastic loyalties. However, masters are expected to keep style secrets out of the hands of unworthy students.4 Monks who practice Pak Hoc have been mistaken for Shaolin for centuries, and are traditionally irritated by this. With the encouragement of the monastic hierarchy, Pak Hok artists are often vocal about the wonderful culture and traditions of Tibet, and seek to make appreciation of Tibetan culture more widespread in other nations. Pak Hok classes aren’t hard to find, but being Trained by a Maste, usually requires spending time in Tibet, and most often, becoming a Buddhist monk.

Despite Pak Hok having been developed independently of the Chinese Crane styles, grudges against the Cranes have been extended to Pak Hok and they are regarded as enemies by the Lizards, the Toads, and especially the Monkeys. The bad blood with Lizards and Toads makes Pak Hok a particularly relentless foe of the Five Venoms.

Common Professions: Bodyguard, martial arts instructor, monk, police officer.

Praying Mantis

“Somebody’s got to do the dirty work, and it isn’t going to be the Buddhist monks.”—Zhang Wei, Praying Mantis master, Yuan Dynasty, 14th century.

There are myriad animal styles that trace their roots back to Shaolin Kung Fu, but only one has stayed fiercely loyal to the Shaolin. The style was invented by 11th century monk Wang Lang, after watching praying mantises when he should have been meditating. The Praying Mantis have a reputation for being ruthless, forsaking the peaceful and compassionate example of the monks, even as they fight the Shaolin’s wars. This reputation is unfair. Mantis are pragmatic, which is part of what makes them so useful, but they still mean to be on the side of good and take their Buddhist values seriously.

It is difficult to find Praying Mantis teachers. Masters pass on their skills only to those they expect to become Kung Fu masters themselves, and to fight for the Shaolin faction in the Kung Fu War. Many Praying Mantis masters work in the military and police, devoting their lives to protecting the public. Suitably honorable and dedicated comrades may be recruited to the Shaolin cause and trained in the secrets of Praying Mantis style.

Praying Mantis are traditional enemies of Crow, Centipede and Scorpion. Because of Centipede and Scorpion’s central role in The Five Venoms, the Mantis have become passionate enemies of the Venoms, and of crime in general. The Mantis are also rivals with the Wudang faction Hsing I Chuan, who also recruit from soldiers and special ops agents. Mantis does recognize that Hsing I Chuan are essentially “good guys” however.

Common Professions: Government agent, police officer, soldier.

Miscellaneous Buddhist Monks and Nuns

“Why is being a bodhisattva like going to a Foo Fighters concert?”

“It’s no substitute for Nirvana, but it’s something”—anonymous.

The Shaolin aren’t the only Buddhist monks who train Kung Fu! All styles listed under Animal Styles are practiced at, and possibly originated from, some Buddhist monastery somewhere in China or South East Asia. Just add Philosophy (Buddhism) and Meditation as style skills to make the style monastic. Other famous monastic styles include Black Tiger (Henan Monastery), Eight Extreme Fists (Nanshan Monastery), Hand of the Wind (Yonghe Lama Monastery), Long Fist (Daxiangguo Monastery), Mad Monkey (Lingyin Monastery), Nine Method (Zongyue Monastery), Plum Blossom Fist (Hanging Temple Monastery), Poking Foot (Jing Tu Monastery), Southern Dragon (Wa Sau Toi Temple), South-North Fist (Thunder Mountain Monastery), Water Boxing (Hoy Hong Monastery).

Common Professions: Beggar, manual laborer, monk.

Shaolin as Villains

The classic fallen Shaolin is a cynical, hedonistic mercenary. The life of a monk is a demanding one, devoid of most of the pleasures of the flesh. Sometimes, monks give into temptation, break their vows, and cash in on their incredible martial arts skills. Whether serving as assassins, bodyguards, enforcers, or instructors, a rogue Shaolin is an invaluable tool for any criminal organization. Typically, the monks indulge enthusiastically in worldly joys, drinking alcohol, eating meat, gambling, and trying to have all the fun money can buy. However, they often find it difficult to shake all elements of their old life. They might keep their head shaved, or abstain from intoxicants, or suffer attacks of merciful feelings.

Kempo and Pak Hok villains have usually been trained by criminal or commercial organizations and have never been part of the Shaolin faction. The effectiveness of these styles is well known enough that they appeal to athletes, tough-guys, and gangsters.

Footnotes

1. Monks have often had to cope with students more impressed by Kung Fu than Buddhism, as reflected in the 1968 Beetle Style song “Come Together” on Monastery Road.

Here come old bald-top. He come grooving serenely.

He got lightning eyeballs. He feel compassion keenly.

He say “Om mani padme hum.” / He bounce right off the wall and parkour all round the room.

Got no attachments. He got silent footfalls.

He know Monkey Finger. He punch big rocks over.

He say, “With our thoughts we make the world.” / He go helicopter. Can you see his legs whirl?

Come together. Right now. Ascetically.

He brick destruction. He got walrus secret.

He make head-butt window. He one spinal cracker.

He say, “There’s no you. There’s no me.

It’s not about Kung Fu. It’s about Shakyamuni.

Come together. Right now. Through Shakyamuni.”

2. Consider the way the monks are characterized in Zhūlì Ānzhou’s 10th century poem, “My Favorite Shaolins”.

Anzan the compassionate, rescuing kittens

Who can quote every word that Chan Huineng has written

And break rocks to pebbles just using his shins. / He is just one of my favorite Shaolins.

Bankei the lazy, his scalp covered in stubble

Who’s always the first to help peasants in trouble

And then when they thank him just turns red and grins. / Bankei is one of my favorite Shaolins.

Issan the drunken who can’t be defeated

Who often falls down but has never retreated

And drives all the monks from the room when he sings.

He’s good fun and one of my favorite Shaolins.

When my rage strikes, when my pride stings, when I’m getting mean.

I simply remember my favorite Shaolins and then I feel so serene.

Little wonder that some dream of running away to Shaolin Temple. Consider Bèi Tailu’s wistful 14th century poem, “In a Shaolin Lotus Garden”.

I’d like to be at the Shaolin Monastery / In a lotus garden practicing Kung Fu.

Oh what delight for every anchorite / As we do the things a Shaolin loves to do.

We would shout and leap around / And throw each other to the ground.

I’d like to be at the Shaolin Monastery / In a lotus garden practicing Kung Fu.

I’ve got a boss (ah-ah). Oh what a toss (ah-ah). / I work all day to satisfy his greed.

I’ve got tax and invoices in stacks. / So I can buy a heap of junk that I don’t need.

Gonna get some robes and shave my head / And go and be a Shaolin instead.

I’d like to be at the Shaolin Monastery / In a lotus garden practicing Kung Fu.

We’ll meditate. Illuminate. / Growing in compassion every day.

We’ll roll and fight and do what’s right / In every single possible way.

We’ll live in sweet simplicity. / Come and be a Shaolin with me.

I’d like to be at the Shaolin Monastery / In a lotus garden practicing Kung Fu.

In a Shaolin lotus garden with you.

3. Wudang routinely suggest non-action as a solution to problems. The approach is encapsulated by the poem “Relax”, attributed to Lao Tsu in the 6th Century BC.

Relax. Don’t do it. That’s the way to Kung Fu it.

Relax. Don’t do it. When you want to Kung…Fu!

Relax. Don’t do it. Just lean on back and Lao Tsu it.

Relax. Don’t do it. Through non-action you will be able to paralyze nerves, shatter bones, set fires, suffocate an enemy or burst his organs.

4. The experiences of Pak Hok masters coming to America to spread Buddhism are reflected in the rock and roll song “Jailhouse Pak Hok” by Melvin Presley, from Heartbreak Kwoon (1956).

A Tibetan monk was sent to county jail. Oh man!

His gentle ways annoyed the local prison gangs.

The tough guys came and told him he was gonna die.

He smiled and said “I know Pak Hok.” Oh my!

Pak Hok! Oh momma, Pak Hok!

Everybody in the whole cell block, couldn’t beat the monk’s Pak Hok.

Gangsters crashing down all around the floor.

The monk was whirlin’, twirlin’ like a one-man war.

Flying fists and feet were goin’ crash, boom, bang.

Piled in the corner were the Mad Crane Gang.

Pak Hok! That crazy Pak Hok!

Everybody in the whole cell block, couldn’t take the monk’s Pak Hok.